There is no limit to the amount of times that I can say Neil Gaiman is a genius. Because no matter how many times I say it, it still will not do justice to this man’s creativity. It has become my literary life ambition to own every single book, short story, film, script, television show, and radio play that Mr. Gaiman has worked on. (Next on my list? The Neverwhere radio play. James McAvoy, Benedict Cumberbatch, Bernard Cribbins, and Natalie Dormer all reading from a Gaiman written script? Perfection.) Especially after reading The Ocean at the End of the Lane.

I’m just going to jump straight in. With the blurb. I don’t usually do this, but this particular blurb captures the essence of this book. Not many blurbs do that:

A middle-aged man returns to his childhood home and is drawn to the farm at the end of the road where, when he was seven, he encountered a most remarkable girl and her mother and grandmother. As he sits by the pond behind the ramshackle old house, the unremembered past comes flooding back – a past too strange, too frightening, too dangerous to have happened to anyone, let alone a small boy.

One of the most amazing things about this book is that the main character isn’t given a name. I didn’t realise until I had finished, but the point-of-view character is simply “I”. Why is this amazing? Because usually the no-name character thing feels contrived, forced, unnatural. Definitely not the case in this instance. There is so much detail about the boy – his personality, family life, interests, history, worries – that the name really isn’t needed. And what’s in a name, anyway? Not much, really. Besides, the lack of name simply adds to the idea that this story is being recollected from the mind of a man looking back at his childhood; you don’t consciously think of your name while remembering because it’s a superfluous detail.

What we do see is an emphasis on the name Hempstock, the family who lived at the end of the lane. Lettie, the little girl who has been eleven for a long time; Ginnie, the mother; and Old Mrs Hempstock. These women are described in such a way that we get a sense of their supernatural powers, their age, and their mystery, but only in the way a seven year old notices these things. Gaiman makes sure that the narrator never oversteps his boundaries. The man was seven when he experienced these events, and as such he could not remember things that a seven year old would not have noticed. He remembered that Lettie made him feel safe. And that her family talked about things that contradicted his views of the world. But he doesn’t question these things, he simply accepts them at face value. The Hempstocks are different from his family, but aren’t all families?

I do not know why I did not ask an adult about it. I do not remember asking adults about anything, except as a last resort.

The man himself

Gaiman also perfectly captures the separateness of the adult world and the world of children. When the main character pulls a worm out of his foot (and later when the Hempstocks pull a hole out of that same foot), he simply accepts it. These things must happen to other people, it can’t just be him. There’s nothing special this worm, he just knows he has to get it out. Children are capable of accepting so many unbelievable things. It’s one of the things I miss most about childhood. The idea that it’s possible to create an entire family history with just a few dolls and your imagination is lost to me. I only have my imaginary friends, now, that exist in words on a page.

This acceptance is exploited, in a good way, so that when we meet our antagonist, Ursula Monkton, we accept that she is the worm that got carried from the field in our main character’s foot. We accept it because he accepts it, but also because Gaiman gives us just enough evidence (that a young boy would have noticed) so that we can believe this fact whole-heartedly.

We catch a glimpse of the adult world. Just a glimpse. We see our main character’s father, through a crack in the curtains, pressing Ursula Monkton up against the mantle while his wife is away. We know, as adults, what’s happening, but the boy doesn’t. And I love those little touches in books based on memory: that what is happening is described, not explained. It makes the story feel more realistic, even if it is a story full of manta wolves and mystical creatures that try and give people want they want in the most hurtful ways.

But the scariest part of this book was that it actually made me properly scared. Books don’t usually scare me. To be fair, I generally don’t choose scary books, but those scenes in all books that are supposed to be suspenseful and terrifying? I can blaze right through. Not this time. And this is what makes me want to read Coraline. If I can get a sense of terror from one scene, I think the tension in that entire novel would be incredible.

This time, as I was reading about a father trying to drown his son in a bathtub of cold water, I was afraid. What kind of monster could do that to his little boy? A seven year old? And the only provocation was the boy telling the truth about his father’s mistress. (Not that I could see that being easily swallowed: “Dad, the woman you’re shagging behind Mum’s back is actually a worm that got into this house through a hole she put in my foot.”)

As the boy pulled on his father’s tie, trying to climb his way to oxygen, I actually felt breathless. Even though you know he’s going to live because he’s remembering all of this, I was still scared for his life. What else had his father done to him, while us readers weren’t there? And all because the boy didn’t like the woman who wasn’t his Mum.

As a final point, before I just descend into Gaimaniac ramblings (Gaimaniac: an avid fan of anything Neil Gaiman has ever put his hand to), I just want to talk about the fallibility of memory at work in this piece. Fallibility of memory is a phrase that I learnt in high school and then relearnt at university. It’s the idea that memory is imperfect; that our emotions can change the way we remember things. And even that we can convince ourselves things happened differently. I’ve done that more times than I can count.

Basically, there’s this scene in which out main character is in the Hempstocks’ house and they’re fixing his dressing gown. The women are snipping at the fabric and as they snip, bits and pieces of the night’s events fall away. This is the night that the father tries to drown our hero. The father turns up, after the Hempstocks have finished snipping, looking for his son, but instead of being cross, he simply hands his son the toothbrush that he “forgot” and goes back home. The Hempstocks rewrote history. Or did they?

There are scenes throughout the book in which our main character’s memory changes as he remembers. Then, once he remembers the original events, those memories disappear below the surface of his subconscious and he is simply remembering what the Hempstocks tell him to. It makes you think: maybe the Hempstocks have been playing around with your memories too.

★★★★★

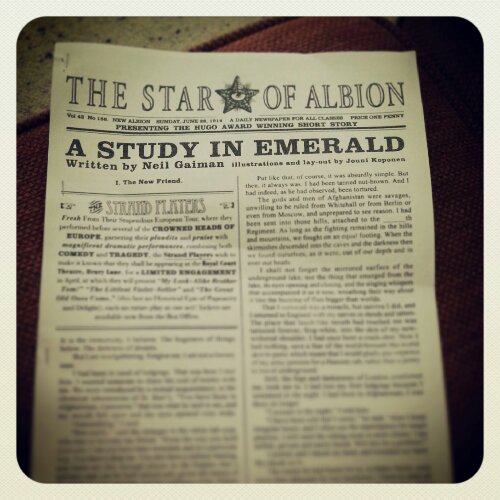

Now leave me alone. I have found, courtesy of thebookboozer, a Gaiman short story entitled A Study in Emerald. Gaiman + Sherlock Holmes. If I don’t surface for a few days, it’s because I died from an overdose of Fangirl.

I love what you said about Gaiman describing events, and not explaining them. It is one of my favorite things about him. He does it in every novel, every short story, absolutely anything he writes. By leaving out the explanation, it is basically his way of saying “because that’s the way it is, obviously”. It makes his unbelievable worlds believable, almost normal. My favorite bit where he does that in this one is the whole fairy ring scene. Lettie is almost annoyed at the boy for not understanding what she was doing, because it was so obvious to her. It made total sense that she needed to get him into that bucket, and because he was a child, he only thought on it for a second. If Lettie was so sure that was what was going to keep him safe, then he would do whatever she asked of him, no matter how crazy it sounded.

Ahhh, I could fangirl over Gaiman all day. Especially A Study in Emerald, and I haven’t even read Doyle’s Sherlock! So good!

Gaiman is brilliant! He is the master of the perfectly constructed story. All of his words mean something. They all work on some other level, besides the superficial. Man, the way he managed to pull off the whole “no explanations” thing in American Gods is nothing short of inspiring. That is one complicated book.

Omg, A Study in Emerald was fantastic! I was so sure it was John writing that the end Blew My Mind.

Only Gaiman *shakes head*

Pingback: “11 Doctors, 11 Stories” – Part Five | My Infernal Imagination

Pingback: The Alphabet Book Tag | My Infernal Imagination